Cellebrite

makes software to automate physically extracting and indexing data from

mobile devices. They exist within the grey – where enterprise branding

joins together with the larcenous to be called “digital intelligence.”

Their customer list has included authoritarian regimes in Belarus,

Russia, Venezuela, and China; death squads in Bangladesh; military

juntas in Myanmar; and those seeking to abuse and oppress in Turkey,

UAE, and elsewhere. A few months ago, they announced that they added Signal support to their software.

Their

products have often been linked to the persecution of imprisoned

journalists and activists around the world, but less has been written

about what their software actually does or how it works. Let’s

take a closer look. In particular, their software is often associated

with bypassing security, so let’s take some time to examine the security

of their own software.

The background

First

off, anything involving Cellebrite starts with someone else physically

holding your device in their hands. Cellebrite does not do any kind of

data interception or remote surveillance. They produce two primary

pieces of software (both for Windows): UFED and Physical Analyzer.

UFED creates a backup of your device onto the Windows machine running UFED (it is essentially a frontend to adb backup on Android and iTunes backup on iPhone, with some additional parsing).

Once a backup has been created, Physical Analyzer then parses the files

from the backup in order to display the data in browsable form.

When

Cellebrite announced that they added Signal support to their software,

all it really meant was that they had added support to Physical Analyzer

for the file formats used by Signal. This enables Physical Analyzer to

display the Signal data that was extracted from an unlocked device in

the Cellebrite user’s physical possession.

One way to think about

Cellebrite’s products is that if someone is physically holding your

unlocked device in their hands, they could open whatever apps they would

like and take screenshots of everything in them to save and go over

later. Cellebrite essentially automates that process for someone holding

your device in their hands.

The rite place at the Celleb…rite time

By

a truly unbelievable coincidence, I was recently out for a walk when I

saw a small package fall off a truck ahead of me. As I got closer, the

dull enterprise typeface slowly came into focus: Cellebrite. Inside, we

found the latest versions of the Cellebrite software, a hardware dongle

designed to prevent piracy (tells you something about their customers I

guess!), and a bizarrely large number of cable adapters.

The software

Anyone

familiar with software security will immediately recognize that the

primary task of Cellebrite’s software is to parse “untrusted” data from a

wide variety of formats as used by many different apps. That is to say,

the data Cellebrite’s software needs to extract and display is

ultimately generated and controlled by the apps on the device, not a

“trusted” source, so Cellebrite can’t make any assumptions about the

“correctness” of the formatted data it is receiving. This is the space

in which virtually all security vulnerabilities originate.

Since

almost all of Cellebrite’s code exists to parse untrusted input that

could be formatted in an unexpected way to exploit memory corruption or

other vulnerabilities in the parsing software, one might expect

Cellebrite to have been extremely cautious. Looking at both UFED and

Physical Analyzer, though, we were surprised to find that very little

care seems to have been given to Cellebrite’s own software

security. Industry-standard exploit mitigation defenses are missing, and

many opportunities for exploitation are present.

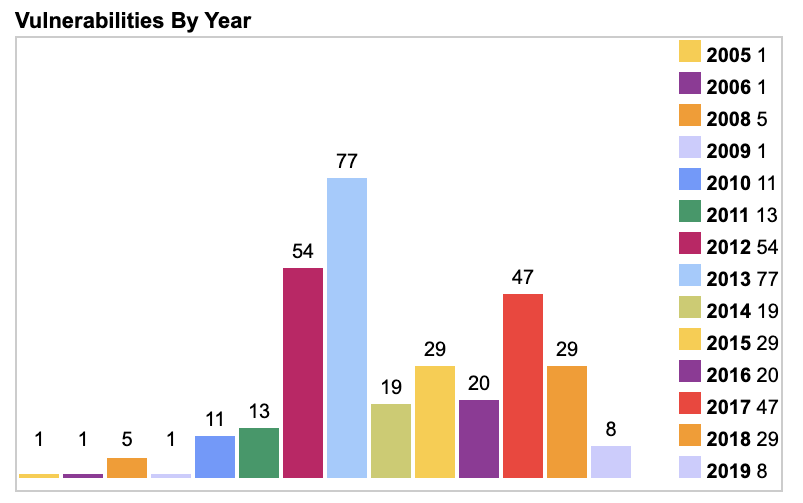

As just one

example (unrelated to what follows), their software bundles FFmpeg DLLs

that were built in 2012 and have not been updated since then. There have

been over a hundred security updates in that time, none of which have been applied.

The exploits

Given

the number of opportunities present, we found that it’s possible to

execute arbitrary code on a Cellebrite machine simply by including a

specially formatted but otherwise innocuous file in any app on a device

that is subsequently plugged into Cellebrite and scanned. There are

virtually no limits on the code that can be executed.

For example,

by including a specially formatted but otherwise innocuous file in an

app on a device that is then scanned by Cellebrite, it’s possible to

execute code that modifies not just the Cellebrite report being created

in that scan, but also all previous and future generated Cellebrite reports from all previously scanned devices and all future scanned devices in

any arbitrary way (inserting or removing text, email, photos, contacts,

files, or any other data), with no detectable timestamp changes or

checksum failures. This could even be done at random, and would

seriously call the data integrity of Cellebrite’s reports into question.

Any

app could contain such a file, and until Cellebrite is able to

accurately repair all vulnerabilities in its software with extremely

high confidence, the only remedy a Cellebrite user has is to not scan

devices. Cellebrite could reduce the risk to their users by updating

their software to stop scanning apps it considers high risk for these

types of data integrity problems, but even that is no guarantee.

We

are of course willing to responsibly disclose the specific

vulnerabilities we know about to Cellebrite if they do the same for all

the vulnerabilities they use in their physical extraction and other

services to their respective vendors, now and in the future.

Below

is a sample video of an exploit for UFED (similar exploits exist for

Physical Analyzer). In the video, UFED hits a file that executes

arbitrary code on the Cellebrite machine. This exploit payload uses the

MessageBox Windows API to display a dialog with a message in it. This is

for demonstration purposes; it’s possible to execute any code, and a

real exploit payload would likely seek to undetectably alter previous

reports, compromise the integrity of future reports (perhaps at

random!), or exfiltrate data from the Cellebrite machine.

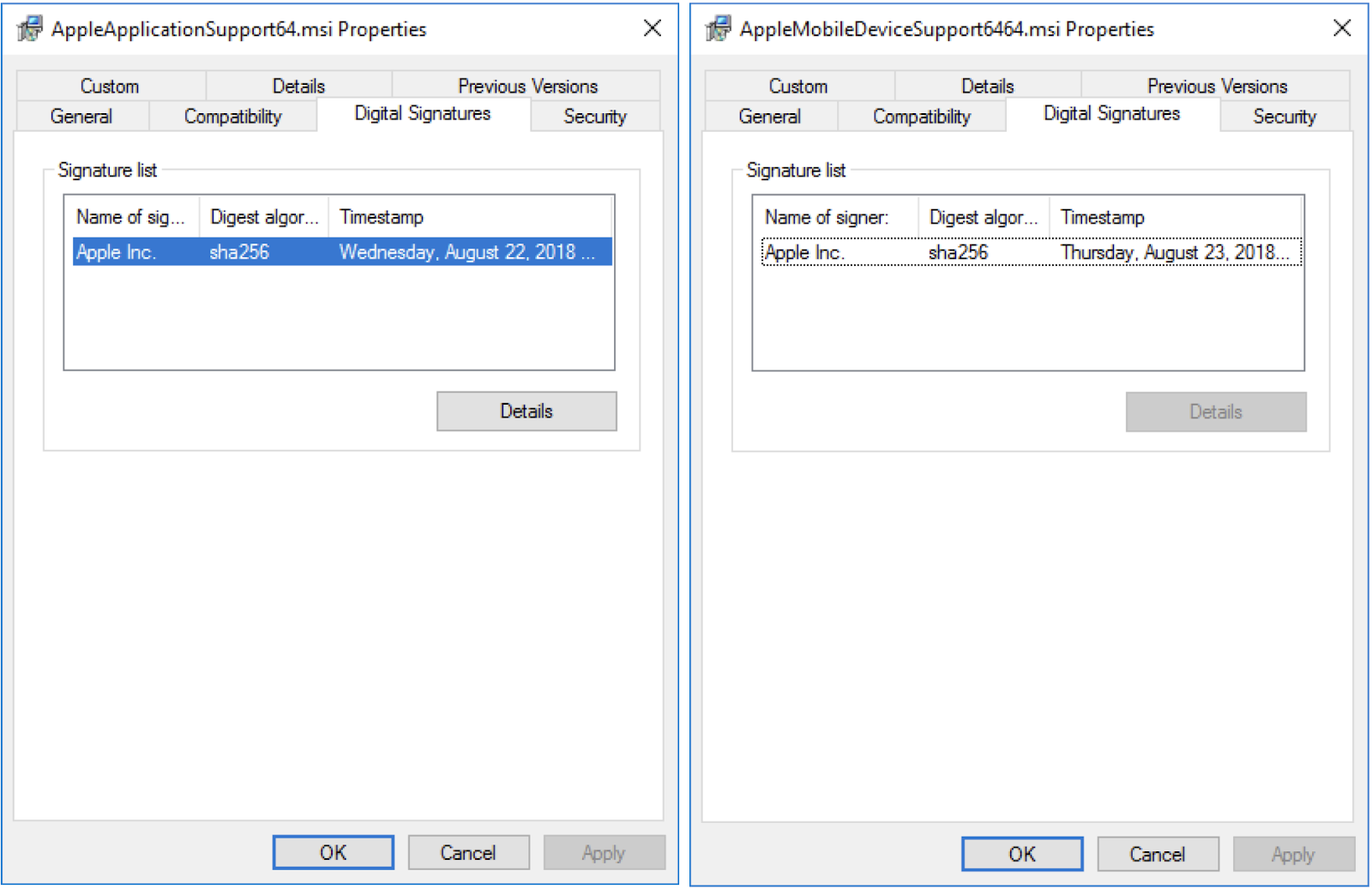

The copyright

Also of interest, the installer for Physical Analyzer contains two bundled MSI installer packages named AppleApplicationsSupport64.msi and AppleMobileDeviceSupport6464.msi.

These two MSI packages are digitally signed by Apple and appear to have

been extracted from the Windows installer for iTunes version

12.9.0.167.

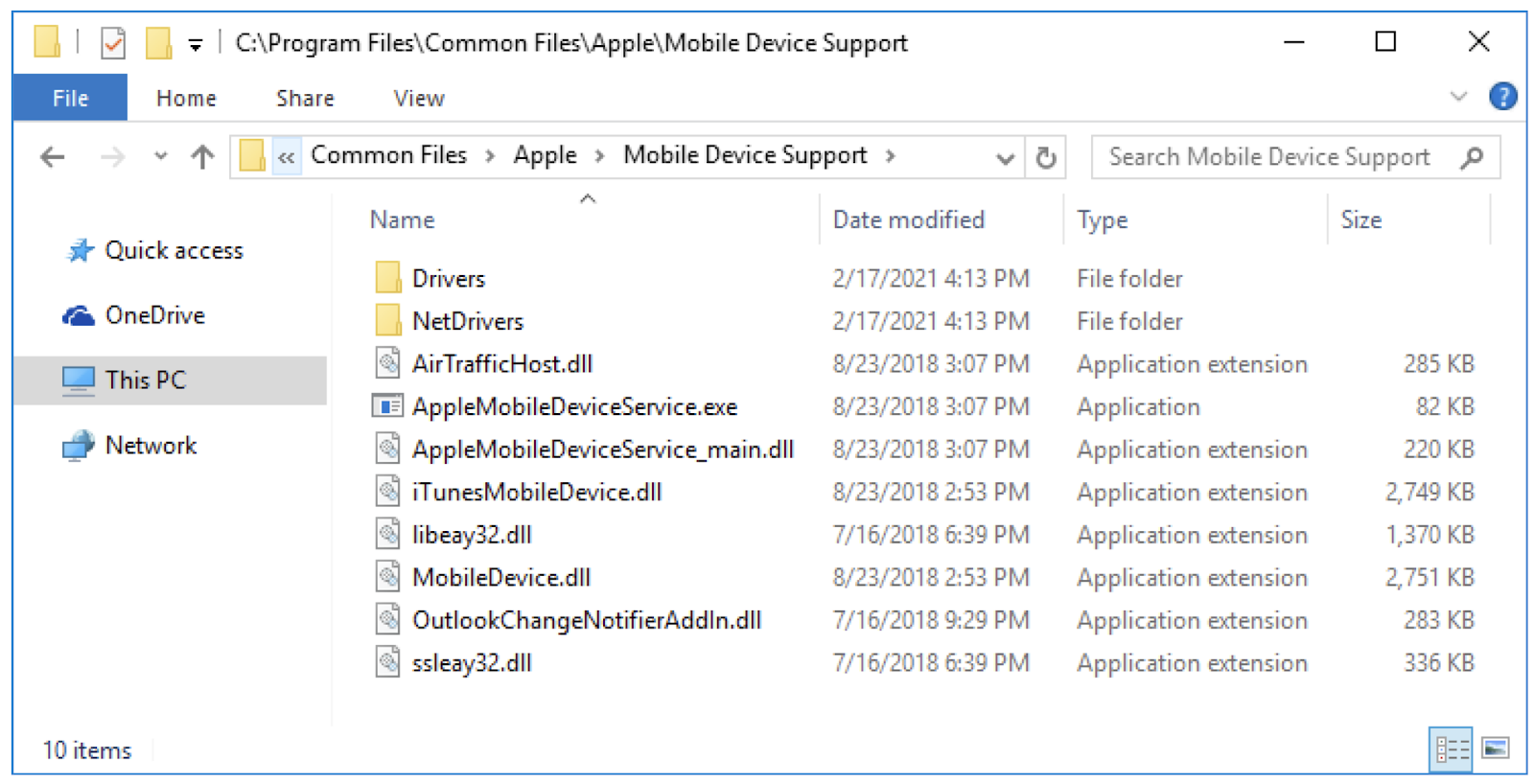

The Physical Analyzer setup program installs these MSI packages in C:\Program Files\Common Files\Apple. They contain DLLs implementing functionality that iTunes uses to interact with iOS devices.

The

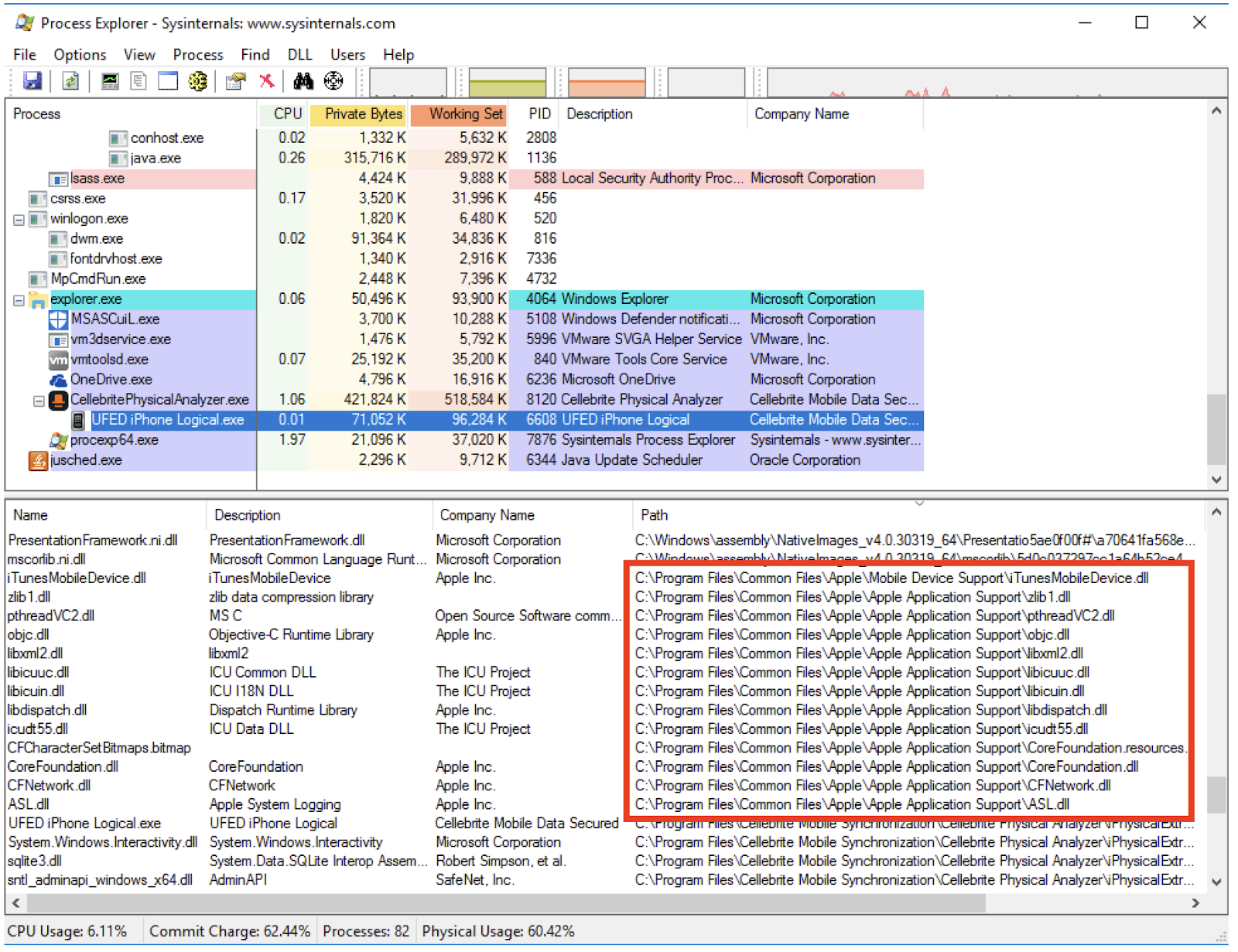

Cellebrite iOS Advanced Logical tool loads these Apple DLLs and uses

their functionality to extract data from iOS mobile devices. The

screenshot below shows that the Apple DLLs are loaded in the UFED iPhone Logical.exe process, which is the process name of the iOS Advanced Logical tool.

It

seems unlikely to us that Apple has granted Cellebrite a license to

redistribute and incorporate Apple DLLs in its own product, so this

might present a legal risk for Cellebrite and its users.

The completely unrelated

In

completely unrelated news, upcoming versions of Signal will be

periodically fetching files to place in app storage. These files are

never used for anything inside Signal and never interact with Signal

software or data, but they look nice, and aesthetics are important in

software. Files will only be returned for accounts that have been active

installs for some time already, and only probabilistically in low

percentages based on phone number sharding. We have a few different

versions of files that we think are aesthetically pleasing, and will

iterate through those slowly over time. There is no other significance

to these files.