In October, Bloomberg Businessweek published an alarming story:

Operatives working for China’s People’s Liberation Army had secretly

implanted microchips into motherboards made in China and sold by

U.S.-based Supermicro. This allegedly gave Chinese spies clandestine

access to servers belonging to over 30 American companies, including

Apple, Amazon, and various government suppliers, in an operation known

as a “supply chain attack,” in which malicious hardware or software is

inserted into products before they are shipped to surveillance targets.

Bloomberg’s report, based on 17 anonymous sources,

including “six current and former senior national security officials,”

began to crumble soon after publication as key parties issued swift and

unequivocal denials. Apple said that “there is no truth” to the claim that it discovered malicious chips in its servers. Amazon said the Bloomberg report had “so many inaccuracies … as it relates to Amazon that they’re hard to count.” Supermicro stated it never heard from customers about any malicious chips or found any, including in an audit it hired another company to conduct. Spokespeople for the Department of Homeland Security and the U.K.’s National Cyber Security Centre said they saw no reason to doubt the companies’ denials. Two named sources

in the story have publicly stated that they’re skeptical of its

conclusions.

But while Bloomberg’s story may well be completely (or partly) wrong,

the danger of China compromising hardware supply chains is very real,

judging from classified intelligence documents. U.S. spy agencies were

warned about the threat in stark terms nearly a decade ago and even

assessed that China was adept at corrupting the software bundled closest

to a computer’s hardware at the factory, threatening some of the U.S.

government’s most sensitive machines, according to documents provided by

National Security Agency whistleblower Edward Snowden. The documents

also detail how the U.S. and its allies have themselves systematically

targeted and subverted tech supply chains, with the NSA conducting its

own such operations, including in China, in partnership with the CIA and

other intelligence agencies. The documents also disclose supply chain

operations by German and French intelligence.

What’s clear is that supply chain attacks are a well-established, if

underappreciated, method of surveillance — and much work remains to be

done to secure computing devices from this type of compromise.

“An increasing number of actors are seeking the capability to target …

supply chains and other components of the U.S. information

infrastructure,” the intelligence community stated in a secret 2009

report. “Intelligence reporting provides only limited information on

efforts to compromise supply chains, in large part because we do not

have the access or technology in place necessary for reliable detection

of such operations.”

Nicholas Weaver, a security researcher of the International Computer

Science Institute, affiliated with the University of California,

Berkeley, told The Intercept, “The Bloomberg/SuperMicro story was so

disturbing because an attack as described would have worked, even if at

this point we can safely conclude that the Bloomberg story itself is

bovine excrement. And now if I’m China, I’d be thinking, ‘I’m doing the

time, might as well do the crime!’”

While the Bloomberg story painted a dramatic picture, the one that

emerges from the Snowden documents is fragmented and incomplete — but

grounded in the deep intelligence resources available to the U.S.

government. This story is an attempt to summarize what that material has

to say about supply chain attacks, from undisclosed documents we’re

publishing for the first time today, documents that have been published

already, and documents that have been published only in part or with

little to no editorial commentary. The documents we draw on were written

between 2007 and 2013; supply chain vulnerabilities have apparently

been a problem for a long time.

None of the material reflects directly on Bloomberg Businessweek’s

specific claims. The publication has not commented on the controversy

around its reporting beyond this statement: “Bloomberg Businessweek’s

investigation is the result of more than a year of reporting, during

which we conducted more than 100 interviews. Seventeen individual

sources, including government officials and insiders at the companies,

confirmed the manipulation of hardware and other elements of the

attacks. We also published three companies’ full statements, as well as a

statement from China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. We stand by our

story and are confident in our reporting and sources.”

Workers build smartphone chip component circuits at the smartphone maker factory in Dongguan, China, on May 8, 2017.

Photo: Nicolas Asfouri/AFP/Getty Images

The U.S. government as a general matter takes seriously the

possibility of supply chain tampering, and of China in particular

conducting such meddling, including during manufacturing, according to

government documents.

A classified 2011 Department of Defense “Strategy for Operating in Cyberspace”

refers to supply chain vulnerabilities as one of the “central aspects

of the cyber threat,” adding that the U.S.’s reliance on foreign

factories and suppliers “provides broad opportunities for foreign actors

to subvert and interdict U.S. supply chains at points of design,

manufacture, service, distribution, and disposal.”

Chinese hardware providers could position themselves in U.S. industry

to compromise “critical infrastructure upon which DoD depends,”

according to the document.

Another classified document, a 2009 National Intelligence Estimate about “The Global Cyber Threat to the US Information Infrastructure,”

assessed with “high confidence” that there was an increased “potential

for persistent, stealthy subversions” in technology supply chains due to

globalization and with “moderate confidence” that this would occur in

part by tampering with manufacturing and by “taking advantage of

insiders.” Such “resource-intensive tactics” would be adopted, the

document claimed, to counter additional security on classified U.S.

networks.

Each National Intelligence Estimate focuses on a particular issue and

represents the collective judgment of all U.S. intelligence agencies,

as distilled by the director of national intelligence. The 2009 NIE

singled out China and Russia as “the greatest cyber threats” to the U.S.

and its allies, saying that Russia had the ability to conduct supply

chain operations and that China was conducting “insider access, close

access, remote access, and probably supply chain operations.” In a

section devoted to “Outside Reviewers’ Comments,” one such reviewer, a

former executive at a maker of communications hardware, suggested that

the intelligence community look more closely at the Chinese supply

chain. The reviewer added:

The deep influence of the Chinese government on their electronics manufacturers, the increasing complexity and sophistication of these products, and their pervasive presence in global communications networks increases the likelihood of the subtle compromise — perhaps a systemic but deniable compromise — of these products.

The NIE even flagged supply chain attacks as a threat to the

integrity of electronic voting machines, since the machines are “subject

to many of the same vulnerabilities as other computers,” although it

noted that, at the time in 2009, U.S. intelligence was not aware of any

attempts “to use cyber attacks to affect U.S. elections.”

Beyond mostly vague concerns involving Russia and China, the U.S.

intelligence community did not know what to make of the vulnerability of

computer supply chains. Conducting such attacks was “difficult and

resource-intensive,” according to the NIE, but beyond that, it had

little information to understand the scope of the problem: “The

unwillingness of victims and investigating agencies to report incidents”

and the lack of technology to detect tampering meant that “considerable

uncertainty overshadows our assessment of the threat posed by supply

chain operations,” the NIE said.

A section within the 2011 Department of Defense Strategy for

Operating in Cyberspace is devoted to the risk of supply chain attacks.

This section describes a strategy to “manage and mitigate the risk of

untrustworthy technology used by the telecommunications sector,” in part

by bolstering U.S. manufacturing, to be fully operational by 2016, two

years after Bloomberg said the Supermicro supply chain attack occurred.

It’s not clear if the strategy ever became operational; the Defense

Department, which published an unclassified version of the same document, did not respond to a

request for comment. But the 2009 NIE said that “exclusion of foreign

software and hardware from sensitive networks and applications is

already extremely difficult” and that even if an exclusion policy were

successful “opportunities for subversion will still exist through front

companies in the United States and adversary use of insider access in US

companies.”

A third document, a page on “Supply Chain Cyber Threats” from Intellipedia, an internal wiki for

the U.S. intelligence community, included classified passages echoing

similar worries about supply chains. A snapshot of the page from 2012

included a section, attributed to the CIA, saying that “the specter of

computer hardware subversion causing weapons to fail in times of crisis,

or secretly corrupting crucial data, is a growing concern. Computer

chips are increasingly complex and subtle modifications made in design

or manufacturing processes could be made impossible to detect with the

practical means currently available.” Another passage, attributed to the

Defense Intelligence Agency, flagged application servers, routers, and

switches as among the hardware likely “vulnerable to the global supply

chain threat” and added that “supply chain concerns will be exacerbated

as U.S. providers of cybersecurity products and services are acquired by

foreign firms.”

A 2012 snapshot of a different Intellipedia page listed supply chain attacks first among threats to so-called air-gapped

computers, which are kept isolated from the internet and are used by

spy agencies to handle particularly sensitive information. The document

also said that Russia “has experience with supply chain operations” and

stated that “Russian software companies have set up offices in the

United States, possibly to deflect attention from their Russian origins

and to be more acceptable to U.S. government purchasing agents.”

(Similar concerns over Russian antivirus software firm Kaspersky Lab led to a recent ban on the use of Kaspersky software within the U.S. government.) Kaspersky

Lab has repeatedly denied that it has ties to any government and said it

would not help a government with cyber espionage. Kaspersky is even reported to have helped expose former NSA contractor Harold T. Martin III, who

was charged with large-scale theft of classified data from the NSA.

Components are seen on a circuit board inside Huawei

Technologies Co.’s S12700 Series Agile Switches on display in an

exhibition hall at the company’s headquarters in Shenzhen, China, on

Tuesday, June 5, 2018.

Photo: Giulia Marchi/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Beyond broad worries, the U.S. intelligence community had some

specific concerns about China’s ability to use the supply chain for

espionage.

The 2011 Defense Department strategy document said, without

elaborating, that Chinese telecommunications equipment providers

suspected of ties to the People’s Liberation Army “pursue inroads into

the U.S. telecommunications infrastructure.”

This may be a reference, at least in part, to Huawei, the Chinese

telecommunications giant that the department feared would create

backdoors in equipment sold to U.S. communications providers. The NSA

went as far as to hack into Huawei’s corporate communications, looking

for links between the company and the People’s Liberation Army, as

reported jointly by the New York Times and the German news magazine Der Spiegel. The report cited no evidence

linking Huawei to the People’s Liberation Army, and a spokesperson from

the company told the publications it was ironic that “they are doing to

us is what they have always charged that the Chinese are doing through

us.”

The U.S. intelligence community appeared concerned that Huawei might

help the Chinese government tap into a sensitive transatlantic

telecommunications cable known as “TAT-14,” according to a top-secret NSA briefing on Huawei.

The cable carried defense industry communication on a segment between

New Jersey and Denmark; a 2008 upgrade was contracted to Mitsubishi,

which “subcontracted the work Out to Huawei. Who in turn upgraded the

system with a High End router of their own,” as the document put it. As a

broader concern, the document added that there were indications the

Chinese government might use Huawei’s “market penetration for its own

SIGINT purposes” — that is, for signals intelligence. A Huawei

spokesperson did not comment in time for publication.

In other documents, spy agencies flagged another specific concern,

China’s growing prowess at exploiting the BIOS, or the Basic

Input/Output System. The BIOS, which is also known by the acronyms EFI

and UEFI, is the first code that gets executed when a computer is

powered on before launching an operating system like Windows, macOS, or

Linux. The software that makes up the BIOS is stored on a chip on the

computer’s motherboard, not on the hard drive; it is often referred to

as “firmware” because it is tied so closely to the hardware. Like any

software, the BIOS can be modified to be malicious and is a particularly

good target for computer attacks because it resides outside the

operating system and thus, cannot be easily detected. It is not even

affected when a user erases the hard drive or installs a fresh operating

system.

The Defense Intelligence Agency believed that China’s capability at

exploiting the BIOS “reflects a qualitative leap forward in exploitation

that is difficult to detect,” according to the “BIOS Implants” section

in the Intellipedia article on threats to air-gapped computers. The section further stated that

“recent reporting,” presumably involving BIOS implants, “corroborates

the tentative view in a 2008 national intelligence estimate that China

is capable of intrusions more sophisticated than those currently

observed by U.S. network defenders.”

A 2012 snapshot of another Intellipedia page, on “BIOS Threats,”

flags the BIOS’s vulnerability to supply chain meddling and insider

threats. Significantly, the document also appears to refer to the U.S.

intelligence community’s discovery of BIOS malware from China’s People’s

Liberation Army, stating that “PLA and [Russian]

MAKERSMARK versions do not appear to have a common link beyond the

interest in developing more persistent and stealthy” forms of hacking.

The “versions” mentioned appear to be instances of malicious BIOS

firmware from both countries, judging from footnotes and other context

in the document.

The Intellipedia page also contained indications that China may have

figured out a way to compromise the BIOS software that’s manufactured by

two companies, American Megatrends, commonly known as AMI, and Phoenix

Technologies, which makes Award BIOS chips.

In a paragraph marked top secret, the page stated, “Among currently

compromised are AMI and Award based BIOS versions. The threat that BIOS

implants pose increases significantly for systems running on compromised

versions.” After these two sentences, concluding the paragraph, is a

footnote to a top-secret document, which The Intercept has not seen,

titled “Probable Contractor to PRC People’s Liberation Army Conducts

Computer Network Exploitation Against Taiwan Critical Infrastructure

Networks; Develops Network Attack Capabilities.”

The word “compromised” could have different meanings in this context

and does not necessarily indicate that a successful Chinese attack

occurred; it could simply mean that specific versions of AMI and

Phoenix’s Award BIOS software contained vulnerabilities that U.S. spies

knew about. “It’s very puzzling that we haven’t seen evidence of more

firmware attacks,” said Trammell Hudson, a security researcher at the

hedge fund Two Sigma Investments and co-discoverer of a series of BIOS

vulnerabilities in MacBooks known as Thunderstrike.

“Most every security conference debuts several new vulnerability

proof-of-concepts, but … the only public disclosure of compromised

firmware in the wild” came in 2015, when Kaspersky Lab announced the

discovery of malicious hard drive firmware from an advanced hacking operation dubbed Equation Group. “Either as an industry we’re not very good at

detecting them, or these firmware attacks and hardware implants are only

used in very tailored access operations.”

Hudson added, “It is quite worrisome that many systems never receive

firmware updates after they ship, and the numerous embedded devices in a

system are even less likely to receive updates. Any compromises against

the older versions have a ‘forever day’ aspect that means that they

will remain useful for adversaries against systems that might be in use

for many years.”

American Megatrends issued the following statement: “The BIOS

firmware industry, and computing as a whole, has taken incredible steps

towards security since 2012. The information in the Snowden document

concerns platforms that pre-date current BIOS-level security. We have

processes in place to identify security vulnerabilities in boot firmware

and promptly provide the mitigation to our OEM and ODM customers for

their platforms.”

Phoenix Technologies issued the following statement: “The attacks

described in the document are well-understood in the industry. Award

BIOS was superseded by today’s more secure UEFI framework which

contained mitigations for these types of firmware attacks many years

ago.”

The Snowden documents reviewed so far discuss, in often vague and

uncertain terms, what U.S. intelligence believes its adversaries like

China and Russia are capable of. But these documents and others also

discuss in much more specific terms what the U.S. and its allies are

capable of, including descriptions of specific, successful supply chain

operations. They also describe in broad strokes the capabilities of

various NSA programs and units against supply chains.

The Intellipedia page on threats to air-gapped networks disclosed that as of 2005, Germany’s foreign intelligence agency, the

BND, “has established a few commercial front companies that it would use

to gain supply chain access to unidentified computer components.” The

page attributes this knowledge to “information obtained during an

official liaison exchange.” The page did not mention who BND’s target

was or what sorts of activities the front companies were engaged in.

BND has been “setting up front companies for both HUMINT and SIGINT

operations since the 1950s,” said Erich Schmidt-Eenboom, German author

and BND expert, using the jargon terms for intelligence gathered both by

human spies and through electronic eavesdropping, respectively. “As a

rule, a full-time BND employee will found a small GmbH [company], which

is responsible for a single operation. In the SIGINT area, this GmbH

also maintains contacts with industrial partners.”

BND did not respond to a request for comment.

The Intellipedia page also stated that, beginning in 2002, France’s

intelligence agency, DGSE, “delivered computers and fax equipment to

Senegal’s security services and by 2004 could access all the information

processed by these systems, according to a cooperative source with

indirect access.” Senegal is a former French colony. Representatives of

the Senegalese government did not respond to a request for comment. DGSE

declined to comment.

Left/Top: Intercepted packages are opened carefully. Right/Bottom: A “load station” implants a beacon.Photos: NSA

Much of what’s been reported about the U.S.’s supply chain attack

capabilities came from a June 2010 NSA document that The Intercept’s

co-founder Glenn Greenwald published with his 2014 book “No Place to

Hide.” The document, an article from an internal NSA news site called

SIDtoday, was published again in 2015 in Der Spiegel with fewer redactions (but without any new analysis).

SIDtoday concisely explained one NSA approach to supply chain attacks (formatting is from the original article):

Shipments of computer network devices (servers, routers, etc.) being delivered to our targets throughout the world are intercepted. Next, they are redirected to a secret location where Tailored Access Operations/Access Operations (AO – S326) employees, with the support of the Remote Operations Center (S321), enable the installation of beacon implants directly into our targets’ electronic devices. These devices are then re-packaged and placed back into transit to the original destination.

Supply chain “interdiction” attacks like this involve compromising

computer hardware while it’s being transported to the customer. They

target a different part of the supply chain than the attack described by

Bloomberg; Bloomberg’s story said Chinese spies installed malicious

microchips into server motherboards while they were being manufactured

at the factory, rather than while they were in transit. The NSA document

said its interdiction attacks “are some of the most productive

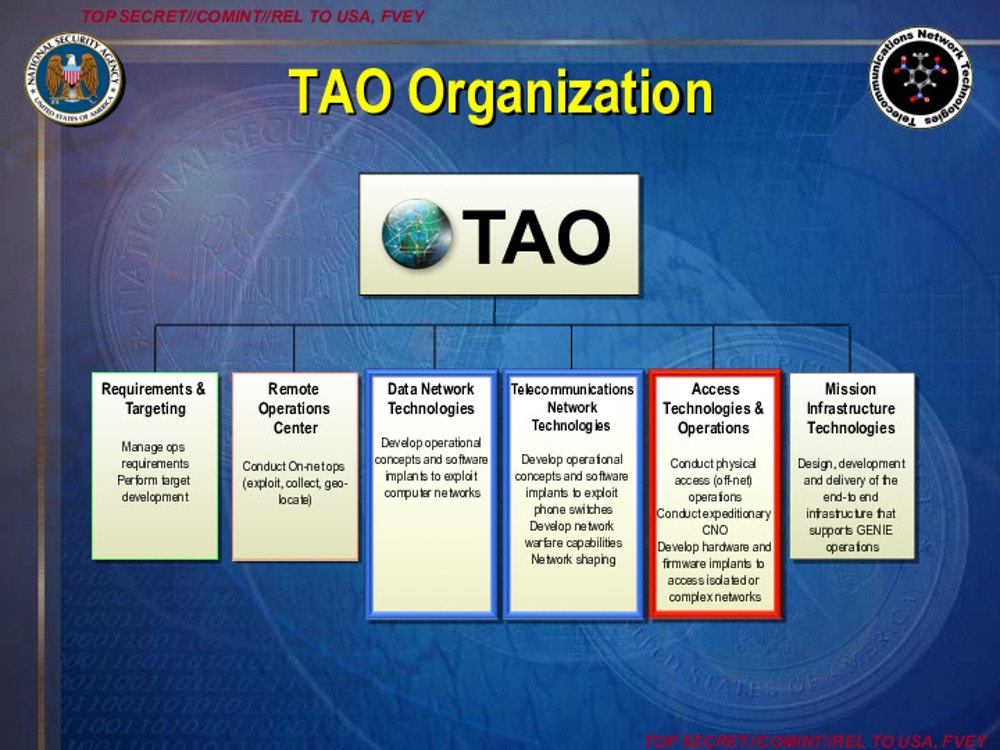

operations in TAO,” or Tailored Access Operations, NSA’s offensive

hacking unit, “because they pre-position access points into hard target

networks around the world.” (TAO is known today as Computer Network

Operations.)

Interdicting specific shipments may carry less risk for a spy agency

than implanting malicious microchips en masse at factories. “A

design/manufacturing attack of the sort alleged by Bloomberg is

plausible,” Eva Galperin, director of cybersecurity at the Electronic

Frontier Foundation, told The Intercept. “That’s exactly why the story

was such a big deal. But just because it’s plausible doesn’t mean it’s

happened, and Bloomberg just didn’t bring in enough evidence, in my

opinion, to support their claim.” She added, “What we do know is that a

design/manufacturing attack is highly risky for the attacker and that

there are many less risky alternatives that are better suited to the

task at hand.”

A Syrian man looks at his mobile phone in the Bustan al-Qasr neighborhood of Aleppo, Syria, on Sept. 21, 2012.

Photo: Manu Brabo/AP

Several months after Syrian Telecom received the devices, one of the

beacons “called back to the NSA covert infrastructure.” At that point,

the NSA used its implant to survey the network where the device was

installed and discovered that the device gave much greater access than

expected; in addition to the internet backbone, it provided access into

the national cellular network operated by Syrian Telecom, since the

cellular traffic traversed the backbone.

“Since the STE GSM [cellular] network has never been exploited, this

new access represented a real coup,” the author of the NSA document

wrote. This allowed the NSA to “automatically exfiltrate” information

about Syria Telecom cellular subscribers, including who they called,

when, and their geographical locations as they carried their phones

throughout the day. It also enabled the NSA to gain further access to

cellular networks in the region.

Document: NSA

Another NSA document describes a different successful attack

conducted by the agency. A slide from a 2013 NSA “program management

review” described a top-secret supply chain operation targeting a Voice-Over-IP network for classified online phone calls. At

an “overseas location,” the NSA intercepted an order of equipment for

this network from a manufacturer in China and compromised it with

implant beacons.

“The analysis and reporting on this target identified, with high

granularity, [the target’s] method of hardware procurement,” stated a

presentation slide. “As a result of these efforts, NSA and its

[Intelligence Community] partners are now positioned for success with

future opportunities.”

In addition to information about specific supply chain operations by

the U.S. and its allies, Snowden documents also include more general

information about U.S. capabilities.

Computer hardware can be altered at various points along the supply

chain, from design to manufacturing to storage to shipment. The U.S. is

among the small number of countries that could, in theory, compromise

devices at many different points in this pipeline, thanks to its

resources and geographic reach.

Document: NSA

This was underlined in a top-secret 2011 presentation about the Special Collection Service, a joint NSA/CIA spying program

operating out of U.S. diplomatic facilities overseas. It referred to 80

global SCS sites as “points of presence” providing a “home field

advantage in [the] adversary’s space,” from which “human enabled

SIGINT,” can be conducted, and where supply chain “opportunities”

present themselves, a suggestion that the NSA and CIA conduct supply

chain attacks from U.S. embassies and consulates around the world. (The

presentation was published by Der Spiegel in 2014, alongside 52 other documents, and apparently

never written about. The Intercept is republishing it to include the

speaker notes.)

One program that goes after computer supply chains in this manner is

the NSA’s SENTRY OSPREY, in which the agency uses human spies to bug

digital intelligence sources, or, as the top-secret briefing published by The Intercept in 2014 puts it, “employs its own HUMINT assets […] to support SIGINT

operations,” including “close access” operations that essentially put

humans right up against physical infrastructure. These operations,

conducted in conjunction with partners like the CIA, FBI, and Defense

Intelligence Agency, appear to have included attempts to implant bugs

and compromise supply chains; a 2012 classification guide said they included “supply chain-enabling” and “hardware

implant-enabling” — as well as “forward-based [program] presence” at

sites in Beijing, as well as South Korea and Germany, all home to

telecommunications manufacturers. Another program, SENTRY OWL, works

“with specific foreign partners… and foreign commercial industry

entities” to make devices and products “exploitable for SIGINT,”

according to the briefing.

The NSA’s Tailored Access Operations played a critical role in the

U.S. government’s supply chain interdiction operations. In addition to

helping intercept shipments of computer hardware to secretly install

hardware implants, one division of TAO, known as the “Persistence

Division,” was tasked with actually creating the implants.

Document: NSA

A 2007 top-secret presentation about TAO described “sophisticated” covert hacking of software,

including firmware, over a computer network “or by physical

interdiction,” and credits these attacks with providing U.S. spy

agencies “some of their most significant successes.”

Another document, a 2007 NSA wiki page titled “Intern Projects,” first published by Der Spiegel, described “ideas about possible future projects for the

Persistence Division.” The projects described involved adding new

capabilities to the NSA’s existing malicious firmware-based implants.

These implants could be inserted into target computers via supply chain

attacks.

One potential project proposed to expand a type of BIOS malware to

work with computers running the Linux operating system and to offer more

ways to exploit Windows computers.

Another suggested targeting so-called virtualization technology on

computer processors, which allows the processors to more efficiently and

reliably segregate so-called virtual machines, software to simulate

multiple computers on a single computer. The proposed project would

develop a “hypervisor implant,” indicating that it intended to target

the software that coordinates the operation of virtual machines, known

as the hypervisor. Hypervisors and virtual machines are used widely by

cloud hosting providers. The implant would leverage support for virtual

machines in both Intel and AMD processors. (Intel and AMD did not

respond to requests for comment.)

Another possible project envisioned attaching a short hop radio to a

hard drive’s serial port and communicating with it using a firmware

implant. Yet another aimed to develop firmware implants targeting hard

drives built by U.S. data storage company Seagate. (Seagate did not

respond to a request for comment.)

Illustration: Oliver Munday for The Intercept

One of the reasons spy agencies like the NSA fear supply chain

compromise is that there are so many places on a typical computer to

hide a spy implant.

“Servers today have dozens of components with firmware and hundreds

of active components,” said Joe FitzPatrick, a hardware security trainer

and researcher. “The only way to give it a truly clean bill of health

is in-depth destructive testing that depends on a ‘gold standard’ good

reference to compare to — except defining that ‘gold standard’ is

difficult to impossible. The much greater risk is that even perfect

hardware can have vulnerable firmware and software.”

The Intellipedia page about supply chain threats lists and analyzes the various pieces of hardware where a computer

could be compromised, including power supplies (“could be set to …

self-destruct, damage the computer’s motherboard … or even start a fire

or explosion”); network cards (“well-positioned to plant malware and

exfiltrate information”); disk controllers (“Better than a root kit”);

and the graphics processing unit, or GPU (“well positioned to scan the

computer’s screen for sensitive information”).

According to the Bloomberg report, Chinese spies connected their

malicious microchip to baseboard management controllers, or BMCs,

miniature computers that are hooked into servers to give administrators

remote access to troubleshoot or reboot the servers.

FitzPatrick, quoted by Bloomberg, is skeptical of the Supermicro story, including its description of how spies exploited the BMCs. But experts agreed

that placing a backdoor into the BMC would be a good way to compromise a

server. In a follow-up story,

Bloomberg alleged that a “major U.S. telecommunications company”

discovered a Supermicro server with an implant built into the Ethernet

network card, which is one of the pieces of hardware listed in the

Intellipedia page that’s vulnerable to supply chain attacks. FitzPatrick

was, again, skeptical of the claims.

After the Bloomberg story was published, in a blog post on Lawfare, Weaver, the Berkeley security researcher, argued that the

U.S. government should reduce the number of “components that need to

execute with integrity” to only the central processing unit, or CPU, and

require that that these “trusted base” components used in government

systems be manufactured in the U.S., and by U.S. companies. In this way,

the rest of the computer could be safely manufactured in China —

systems would work securely even if components outside the trusted base,

such as the motherboard, carried malicious implants. Apple’s iPhone and

Intel’s Boot Guard, he argued, already work in this way. Due to the

government’s purchasing power, “it should be plausible to write supply

rules that, after a couple years, effectively require that U.S.

government systems are built in a way that resists most supply chain

attacks,” he told The Intercept.

While supply chain operations are used in real cyberattacks, they

seem to be rare compared to more traditional forms of hacking, like

spear-phishing and malware attacks over the internet. The NSA uses them

to access “isolated or complex networks,” according to a 2007 top-secret

presentation about TAO.

“Supply chain attacks are something individuals, companies, and

governments need to be aware of. The potential risk needs to be weighed

against other factors,” FitzPatrick said. “The reality is that most

organizations have plenty of vulnerabilities that don’t require supply

chain attacks to exploit.”

Documents published with this article: